What AI Memory Is and How It Can Make Your Work More Effective

A practical guide to understanding how AI memory works, and how to turn it into a real advantage in your daily workflow.

Ciao,

This week’s newsletter is arriving a day later than planned. My goal was to publish every Thursday, but the topic turned out to be far less straightforward than I expected, and I ended up rewriting the whole piece several times before it felt clear enough.

This article is part of the ongoing series on AI agents. Memory is one of the most critical components in building an agent, and it’s worth understanding how it actually works before diving into more advanced design patterns.

Today’s issue focuses on memory inside a conversational assistant. These systems provide a surprisingly rich set of features that allow us to manage memory effectively, often without dealing with any technical details ourselves.

Nicola ❤️

Table of Contents

Understanding AI - What AI Memory Is and How It Can Make Your Work More Effective

Curated Curiosity:

The Future of Listening: Qualitative Research at Scale According to Anthropic

Understanding AI

What AI Memory Is and How It Can Make Your Work More Effective

Imagine you are a manager who has to welcome a young colleague who is brilliant, motivated, and has excellent learning abilities. On the first day of work, you greet him, walk him to his desk, and ask him to get started right away. No introductory document, no onboarding meeting, no explanation of expectations. Just a generic request: “Write me a report on this month’s sales; here are the data.” And you hand him a spreadsheet full of codes and figures that might be amounts.

No new hire would be able to carry out the task without context. And I am willing to bet that as you read this description, you thought: “Well, of course. Who would treat a new colleague that way?”

Now imagine that the new hire is an artificial intelligence. How many of you have opened ChatGPT, or another conversational assistant, and started making requests? Perhaps by uploading a spreadsheet with no additional context, accompanied only by a few sparse instructions, and expecting the model to produce a flawless report, ready to hand over to your boss?

Unfortunately, as with humans, we cannot expect good results from AI unless we provide it with adequate context to begin with.

Moreover, when dealing with artificial intelligence, we must remember that it is not truly “intelligent” in the way we usually understand the term. The technology we use every day through ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, and similar tools—namely Large Language Models (LLMs)—does not understand, interpret, or process concepts; it does not possess real-world knowledge. Knowledge, in fact, requires structure, intentionality, and the ability to attribute meaning. Qualities that, for now, belong only to human beings.

However, because language models can produce fluid, coherent texts, we tend to project onto them a competence they do not actually possess. It almost feels natural to expect them to “figure things out,” grasp nuances, and fill in the gaps in an incomplete context, as an experienced colleague would. But this is not the case.

The result is that many users end up disappointed, not because AI works poorly, but because they assign it tasks without providing the necessary elements to carry them out. Just like that, the young new hire was left alone in front of an indecipherable spreadsheet.

The only way to obtain real value from these tools is to reverse our perspective: we must not expect the machine to compensate for the absence of context; we must be the ones to build it. Clear documents, precise instructions, explicit goals, relevant examples—these are the pieces of information needed to complete and guide the memory that an LLM has acquired during training.

The World’s Memory: What LLMs Have Learned During Training

Large Language Models are trained on vast corpora of documents, through which they accumulate a collective “memory of the world.” This memory, however, is not universal. On the contrary, it is essential to note that most of the sources come from WEIRD contexts (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic), with a strong predominance of the Anglosphere. As a result, the representation of the world embedded in the most widely used models is inevitably skewed toward Western—particularly American—perspectives. AI does not “know” the world in a neutral sense; it knows the world as described by the cultures that produce most digital content.

This is, in essence, our starting point. Our artificial colleague resembles a young Western professional: highly educated, well-resourced, and strongly exposed to democratic values. A bright graduate straight out of an American or European campus, enthusiastic and well-prepared, yet still lacking the experience required to navigate autonomously a context that remains unfamiliar.

In addition, a language model's memory, while non-universal, cannot be updated in real time. Every LLM has a cutoff date, the moment when training ceases, and the model is released to the public. Beyond that temporal threshold, the model has no representation of the world: it has not read the news, followed regulatory developments, or absorbed the most recent cultural or technological changes. It therefore requires a dynamic memory, one that enables the model to bridge the gap between its static knowledge and the continuously evolving reality in which we operate daily.

This dynamic memory relies on Internet searches and allows AI systems to retrieve recent, up-to-date, and contextually relevant information when a request is made. It is a non-persistent memory: the model does not retain what it finds; instead, it consults online sources each time we ask it. It is the equivalent of a collaborator who briefly opens an article, an institutional website, or a database to verify a detail before continuing their work.

Conversational assistants do not automatically trigger an online search every time they receive a question. Activation depends on internal signals that differ from model to model but generally include:

references to recent dates or temporal events (“this year,” “today,” “last week”);

requests for updated data, statistics, or indicators that change over time;

mentions of dynamic entities (prices, software versions, weather conditions, news);

prompts that explicitly require external verification.

When no such signals are detected, the model may attempt to answer relying solely on its static memory, generating responses that are plausible but not necessarily accurate. This is one reason why, if we want reliable results, explicit activation of an online search is often necessary.

To ensure that the model draws on an updated memory of the world, it is useful to specify this clearly in the prompt. For example:

“Before responding, carry out an online search and verify the most authoritative sources.”

“Consult the available scientific literature and cite the relevant studies.”

“Update any data used by comparing it with publications from the past two years.”

This explicit instruction not only reduces the risk of error but also allows us to guide the quality of the sources: we may request that the model prioritise academic documents, institutional datasets, official regulations, or professional journalism.

Naturally, relying on online search requires the same critical assessment of sources we would apply to any search engine results. The responsibility for evaluating the reliability of the retrieved information, therefore, remains with the user, who must validate the material and decide how to integrate it into their decision-making process.

Session Memory: How LLMs Manage a Conversation

The conversational assistant manages session memory and enables the LLM to “follow the thread” of the dialogue, recalling what has been said so far and behaving coherently. With each new message, the assistant sends the model our latest input, along with all previous exchanges, concatenated in chronological order.

This allows the model to “see” the full conversation script and respond consistently with what has already been discussed. The technique, however, has an inherent limitation: models can process only a finite amount of information at once, the so-called context window. When a conversation becomes long, older messages are either truncated or summarised to make room for more recent ones. This is when we get the impression that the AI is “forgetting” something. In reality, those pieces of information are no longer present in the prompt, and the model cannot take them into account.

We can influence the content of session memory by providing more or fewer details in our messages, or by attaching documents and images. Yet precisely because this form of memory is transitory and entirely dependent on the prompt, the responsibility for keeping it coherent and informative lies entirely with the user. In other words, we must consciously decide what should remain within the system’s operational memory and what can be omitted.

It follows that, to obtain practical answers, it is often necessary to repeat or summarise key points, to structure information carefully, and to adopt an incremental and orderly form of communication. Each relevant element should be considered not merely as data to transmit, but as a component to be positioned within a conversation that, despite appearing continuous, is always reconstructed one prompt at a time, within the narrow—yet manageable—boundaries of the context window.

Personal Memory: What We Want AI to Remember About Us in the Long Term

Unlike session memory, personal memory is designed to persist over time. It is likewise managed directly by the conversational assistant and consists of a stable collection of information extracted from past interactions, stored and associated with the user’s account. These preferences allow the AI to progressively adapt to your way of expressing yourself, recall your recurring interests, and maintain your preferred formats.

This memory can include a variety of elements, such as:

stylistic or linguistic preferences (“I prefer concise answers,” “write in formal Italian”),

basic demographic or professional details (role, sector, area of activity),

references to recurring projects, clients, or tools you use,

access to the history of past conversations (when enabled).

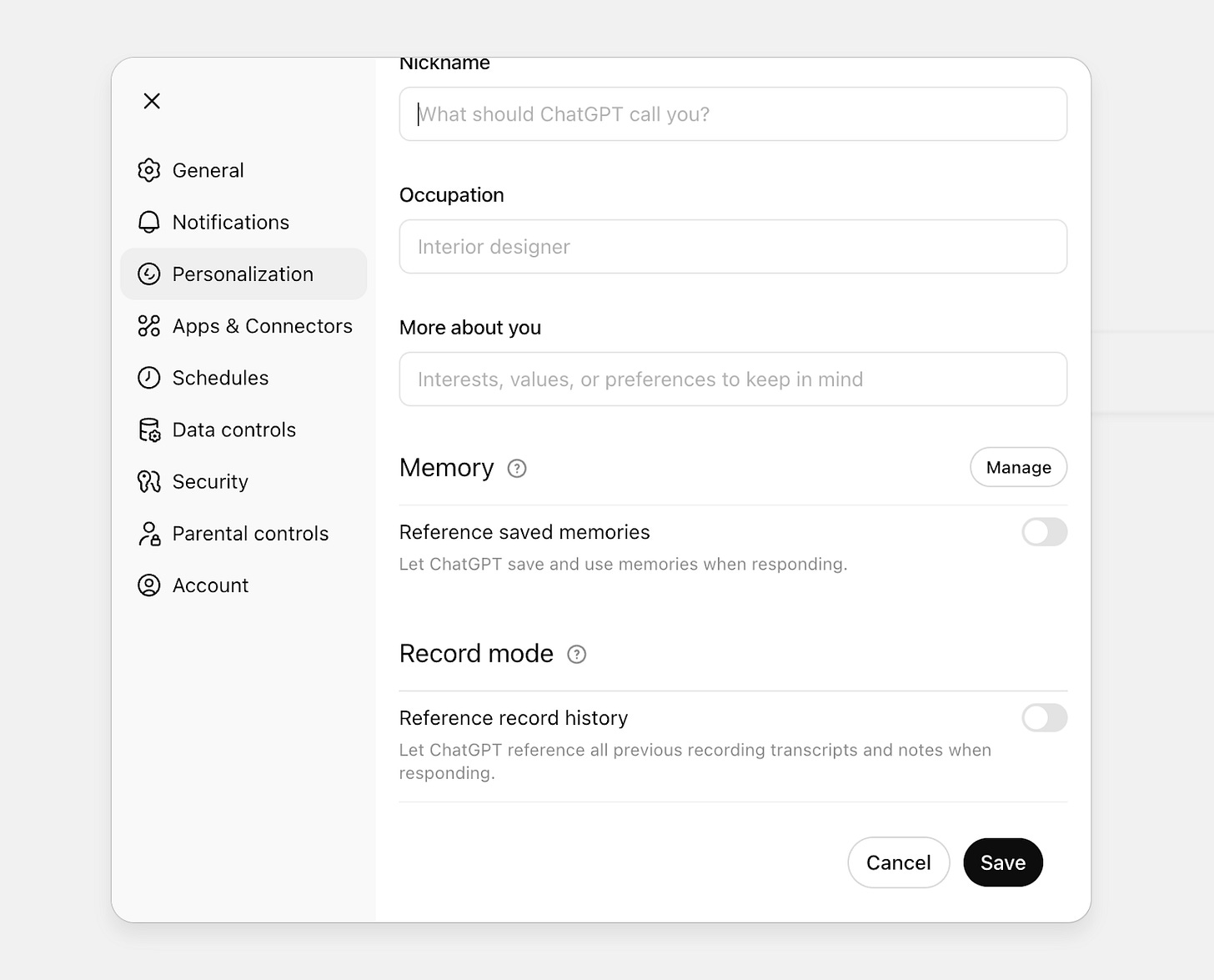

In ChatGPT, this memory can be managed in the Personalization menu, where users may also enable access to all previous conversations.

It is essential to underline that this memory is customizable and revocable. At any time, the user may:

review what has been stored,

update or correct inaccurate information,

temporarily disable the personal memory function,

delete it entirely, thereby resetting the history.

This form of memory can make the interaction with the assistant more fluid, familiar, and efficient. However, for it to work effectively, it requires some maintenance. ChatGPT, for instance, autonomously decides what to remember, and the information it selects is not always relevant or valuable in the long term. Moreover, the available space is limited: memory tends to fill up quickly, and if you want the system to continue learning new aspects of you, you need to clean or reorganize previously stored data periodically.

Alongside permanently saved information, some assistants also allow searching through past conversations and reusing relevant excerpts from earlier exchanges to answer new prompts. This function is available only when memory is enabled, and the user has authorized access to the full chat history. Retrieval may occur automatically or upon explicit request (“check if we have already discussed this,” “resume the conversation about project X”).

As for my own experience, I have found this process overly cumbersome and have preferred to disable both memory and access to the full conversation history.

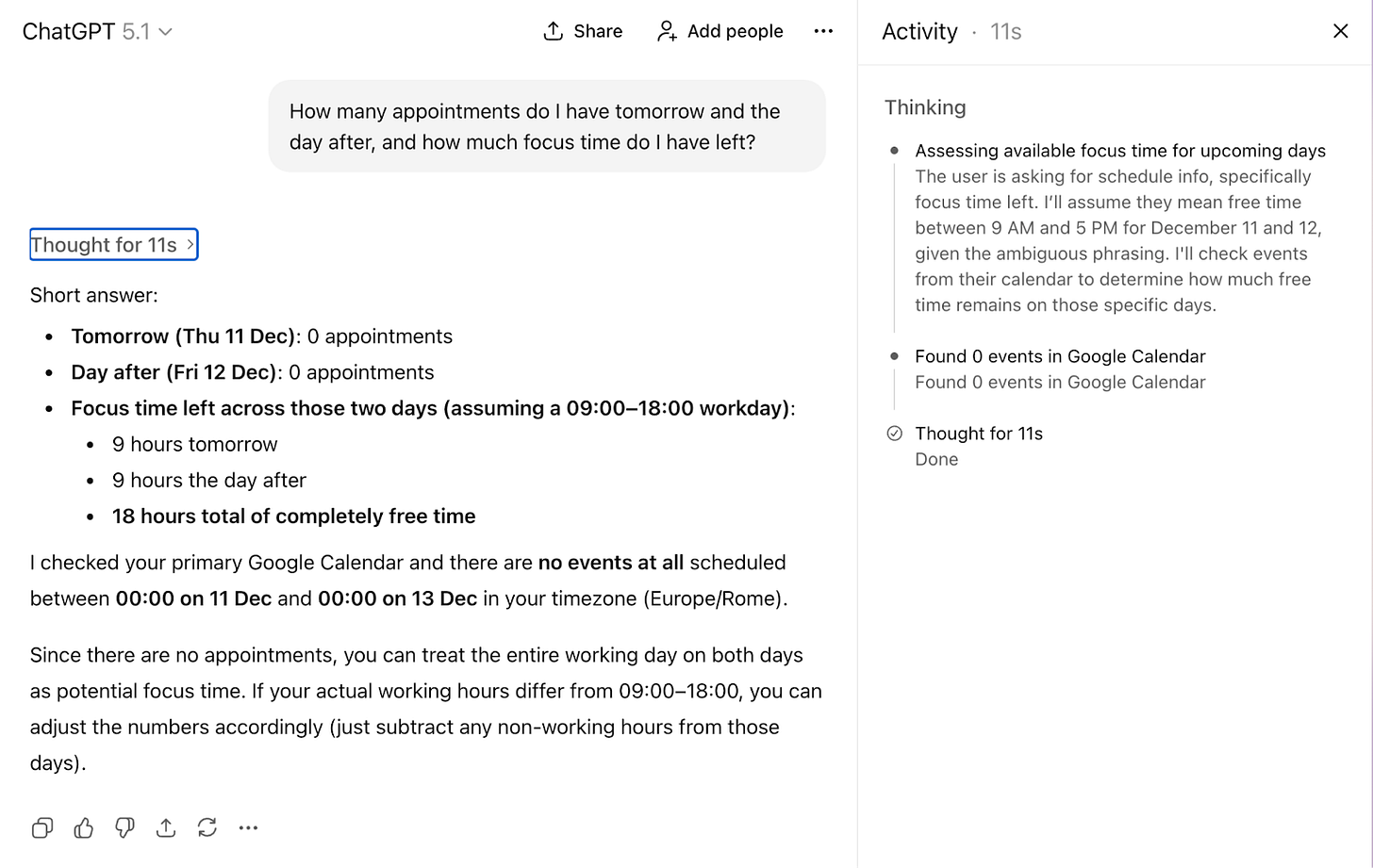

Accessing the Memory Contained in the Tools We Use Every Day

One of the most significant breakthroughs in the practical use of artificial intelligence is the ability to integrate it with the tools you already use daily: email, calendars, cloud storage, notes, and task managers. When this happens, the conversational assistant becomes an intelligent extension of your working environment.

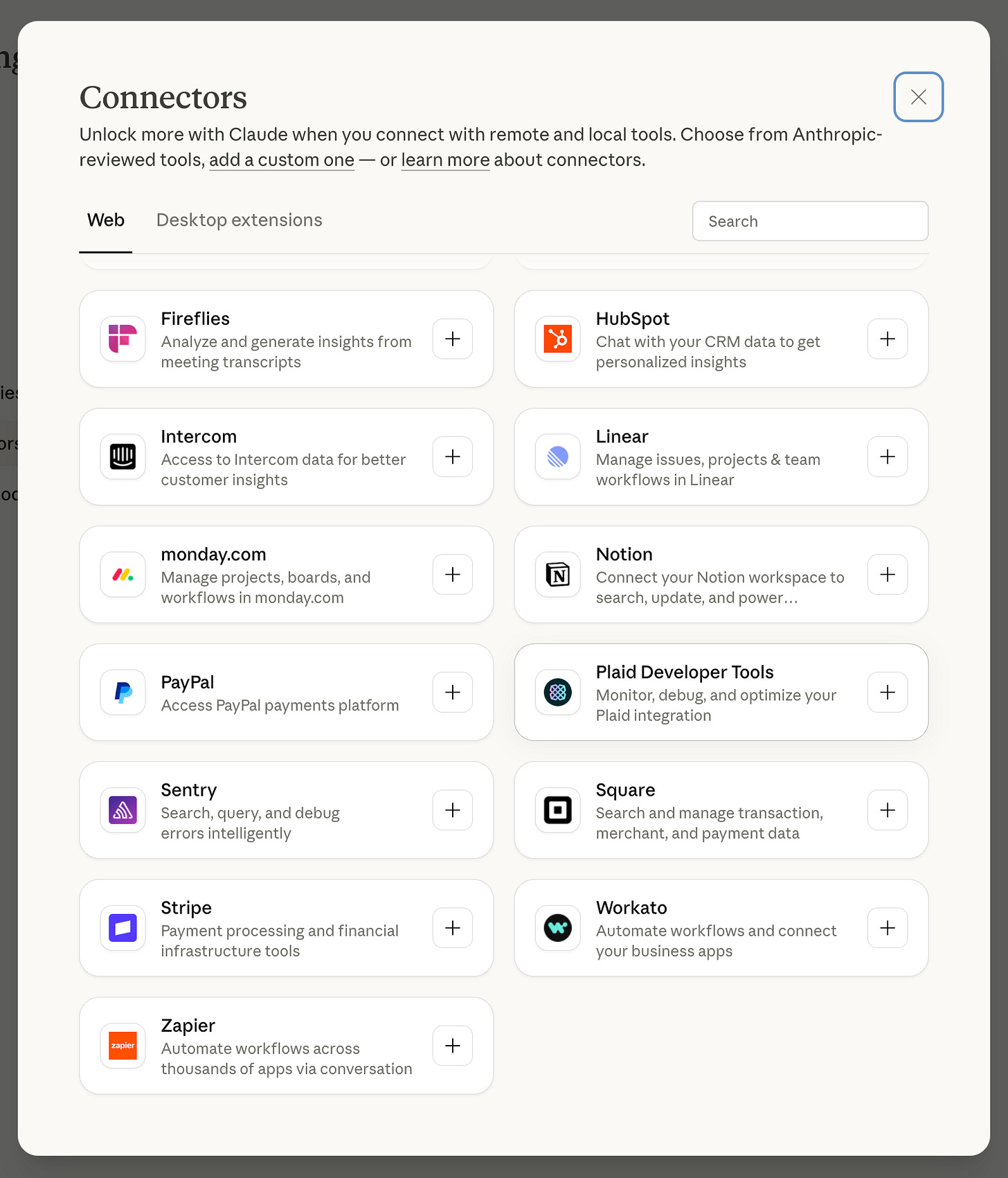

This form of external personal memory is activated through connectors: modules that authorize the AI to access data stored on third-party platforms such as Google Drive, Microsoft 365, Notion, Dropbox, Slack, Trello, and many others. Once connected, these tools can be queried and navigated directly in natural language.

Here are some concrete examples of what becomes possible:

“Check my calendar and tell me when I have a free hour for a call this week.”

“Search my Drive for the presentation I used for the September pitch.”

“Summarize today’s emails that include attachments.”

“Find the notes for project X and compare them with last week’s.”

In all these cases, the AI does not store the contents directly; instead, it accesses them in real time, indexing and interpreting them as needed. Naturally, for this type of memory to function effectively, it requires careful configuration of permissions and accessible sources, as well as high-quality information stored across your personal tools.

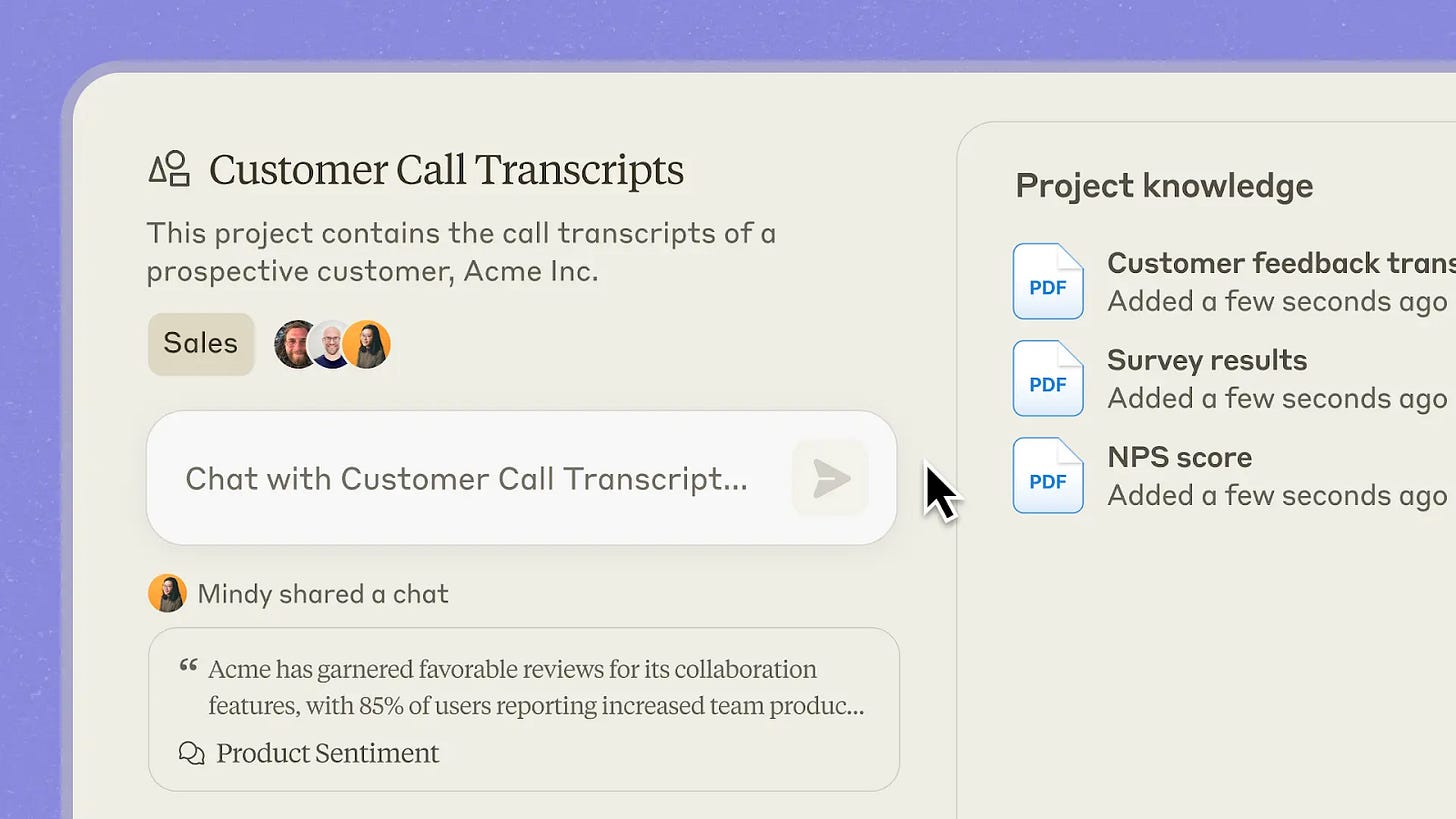

Project Memory: Integrating AI into the Team’s Workflow

When working on a structured initiative, it is no longer sufficient for artificial intelligence to know our personal preferences or access our individual documents. Something more robust is needed: a project memory capable of gathering, organizing, and maintaining, over time, everything relevant to a specific purpose.

To address this need, tools such as ChatGPT and Claude have introduced projects: dedicated containers for managing specialized memories, designed to support complex activities. Similar mechanisms exist in Custom GPTs or in Anthropic’s Skills.

In all these cases, the user can:

upload documents containing reference materials;

define rules and instructions for how the AI should behave within the project’s context;

update the context dynamically, modifying or replacing elements of memory over time.

For example, in an editorial project, the AI can access outlines, previous briefs, published material, and stylistic references; in a marketing campaign, it can consult historical performance data, demographic targets, and archives of past campaigns—both from the brand in question and from its competitors.

One of the main advantages of project workspaces is the ability to share them with other team members, provided a business account with collaborative features is being used. In this way, memories become shared resources: accessible and updatable by multiple people working toward the same objective.

Organizational Memory: Accessing Company Databases Through Connectors

Up to this point, we have discussed features designed for individual use of AI: personal preferences, conversation history, and cloud storage. All elements that remain closely tied to a single user. Only projects within enterprise versions can be shared with colleagues.

Yet most of an organization’s information resides in its databases: the CRM, the ERP, and the systems that track sales, contracts, suppliers, subscriptions, and operational metrics. These archives constitute the company’s memory. And if we want AI to become a genuine work tool, we must give it access to this memory.

There are two ways to achieve this. The first is the most rudimentary: exporting the necessary data each time and manually providing it to the AI as Excel or CSV files, either within a session or within a project. This works, but it is cumbersome and hardly scalable.

The second method involves using a dedicated connector that allows the AI to query company systems directly. This approach is far more effective because it enables the model to translate a request expressed in natural language into a structured query. Questions such as “How many customers spent more than a certain amount in the past six months?” presuppose an interrogation logic that depends entirely on how the underlying database is designed. A connector can embed this knowledge and automatically convert the user’s request into an appropriate SQL query.

If your organization relies on proprietary solutions, the development team will need to build the necessary connectors. Conversely, if you use widely adopted SaaS platforms, the conversational assistant may already provide ready-to-use integrations.

Alternatively, you can rely on an integration platform such as Zapier or Workato, which acts as an intermediary layer and offers preconfigured connectors for thousands of online services.

A Memory for Every Purpose

Understanding the different forms of memory that can be activated in a conversational assistant is essential to turning it into a genuine digital collaborator. Most of the memory types described do not require advanced technical skills: it is enough to be aware of them, understand how they work, and develop a strategy to feed and use them effectively. Even at this basic level, it is possible to achieve significantly better results than those obtained through the generic and uninformed use that still characterizes most interactions with AI.

The next step, however, requires specialists skilled in technologies such as Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), knowledge graphs, and ontologies. These tools enable us to go beyond simple access to data and instead build real knowledge architectures, systems capable not only of storing information but also of organizing, interconnecting, and putting it at the service of more advanced decision-making processes.

I will discuss these topics in an upcoming issue of Radical Curiosity, dedicated to how information can be transformed into knowledge.

Curated Curiosity

The Future of Listening: Qualitative Research at Scale According to Anthropic

Anthropic has been experimenting with a new idea: what if AI could dramatically expand an organization’s ability to listen?

Their tool, Anthropic Interviewer, automates the entire qualitative research process, generating questions, conducting interviews, and analyzing transcripts. In just a few days, it handled 1,250 interviews about how professionals use (and emotionally relate to) AI in their daily work.

What makes this interesting is not only the technology, but the method: a scalable way to capture doubts, aspirations, and shifting professional identities, insights that rarely surface in dashboards or surveys.

A few patterns emerged clearly:

People say they use AI as support, not as a whole delegation. Yet usage data shows automation and assistance are almost balanced. There’s a gap between perception and reality.

Creatives use AI but hide it, fearing it diminishes the perceived value of their work.

Scientists are rigorous, adopting AI for preparatory tasks but excluding it from tasks that require critical judgment.

Across all groups, identity defines delegation: we automate what feels peripheral, and defend what feels core to who we are professionally.

The broader point is powerful: AI can help organizations listen at scale, revealing tensions and expectations that traditional research methods often overlook. This matters for companies designing policies, startups validating products, and public institutions shaping informed regulation.

I tested the tool myself. The interview flowed naturally, deepened at the right moments, and even surfaced themes I hadn’t anticipated. It felt like speaking with a genuinely skilled qualitative researcher — just infinitely faster.

If innovation must start with real listening, tools like this won’t replace human research, but they will expand it in ways that were previously impossible.

Introducing Anthropic Interviewer: What 1,250 professionals told us about working with AI