Practical Guide to AI Agents: How They Work and How to Integrate Them into Daily Work

A new series to help teams understand how AI agents work—and how to design them as reliable collaborators inside real-world workflows.

Ciao,

The article I published last week was unexpectedly well received—it even got picked up by TLDR AI. As a result, the newsletter saw a 10% spike in subscribers. So, to all the new readers: welcome! I hope I’ll live up to your expectations.

This week, I’m kicking off a new series dedicated to AI agents—how to design them properly and how to integrate them into your team as actual coworkers. Today’s piece is a broad introduction. In the coming weeks, I’ll dive into more hands-on tutorials to explore design patterns, workflows, and orchestration strategies.

Nicola ❤️

Table of Contents

Understanding AI - Practical Guide to AI Agents: How They Work and How to Integrate Them into Daily Work

Curated curiosity:

The Future of Language Tech is Platformized, Not Tool-Based

Understanding AI

Practical Guide to AI Agents: How They Work and How to Integrate Them into Daily Work

In the past two years, the term “AI agent” has become increasingly widespread, yet its usage is often vague—if not outright misleading. Agents are frequently described as autonomous and intelligent entities, but in practice, it is essential to adopt a clearer, more concrete model.

This guide aims to provide a concise yet structured understanding of what an AI agent truly is and how it can be used to build operational solutions. It begins with a crucial distinction:

Every agent is composed of three core elements (prompt, context, and tools), which define what the agent is technically capable of doing.

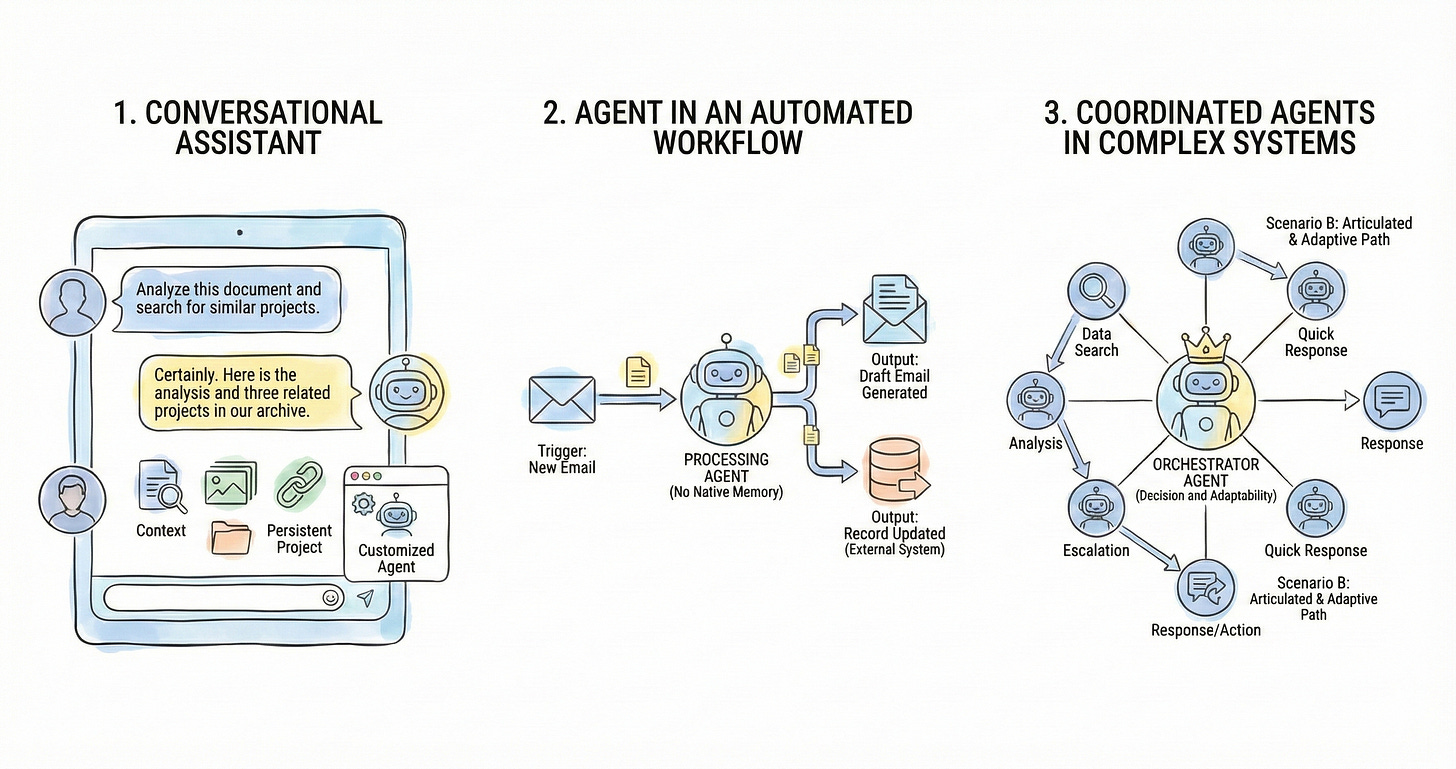

An agent—regardless of its level of complexity—can operate in three distinct modes (as an assistant within a client, as a step in an automated process, or within systems of coordinated autonomous agents).

One must first grasp the agent’s capabilities before exploring how it can be deployed within workflows, applications, or tools already in use.

1. The Core Elements of an AI Agent

Let us imagine welcoming an intern into our team. No one would expect them to deliver results on day one without first explaining what they are supposed to do, providing the right tools, or creating the basic conditions for them to work. Typically, we ensure they have at least some basic skills, orient them towards the objectives, provide them with a computer, share documents, and explain how internal processes work.

The same principle applies to AI agents. Although the underlying model may possess “general” knowledge of the world, it is entirely unfamiliar with our specific context: it does not know our organization’s data, it has no access to the software we use daily, and it is unaware of our operational goals. If we begin to think of agents as interns to be integrated into a team, designing ways to make them effective becomes significantly more straightforward.

Every agent, even the most basic one, is a design-driven combination of three fundamental components: the prompt (which defines what it should do), the context (which provides supporting information), and the tools (which enable it to take action). Let us examine each of them in turn.

1.1. The Prompt and Reasoning

The prompt is the set of instructions and constraints that defines what the agent is expected to do. It can be straightforward—for example: “determine the sentiment of the message”—but in most cases, such a minimal approach yields generic or inconsistent results. It is not enough to ask; one must clearly explain the desired outcome.

To understand this, let us return to the intern analogy: no one would expect them, on their first day, to write a report without knowing the intended audience, which data to use, what tone to adopt, or in what format to deliver it. The same principle applies to an AI agent: an effective prompt is a well-crafted assignment that clarifies roles, objectives, style, output structure, and constraints.

To design high-quality prompts, the Prompt Canvas can be helpful. This framework supports the breakdown and formalization of all the elements contributing to the agent’s behavior. The canvas includes, among other aspects:

the role the agent should assume (“you are a legal advisor,” “you are a data analyst”);

the step-by-step task description;

the informational context;

the intended goals;

the tone and style of the response;

the output format (a table, a summary, a bullet-point list, etc.);

any constraints (avoid technical jargon, do not make unsupported assumptions, etc.).

This approach offers at least two key advantages. On the one hand, it transforms prompting from a trial-and-error activity into a structured, replicable, and modular design practice. On the other hand, it enhances the quality and consistency of the outputs: a well-constructed prompt, supported by the canvas, generates responses that are more coherent, relevant, and aligned with expectations.

Nonetheless, it is essential to remember that the agent’s ability to interpret instructions and produce coherent outputs correctly does not depend solely on the quality of the prompt. Still, also crucially on the underlying language model (LLM) that the agent relies on. Not all models possess the same capabilities: some are designed for simple tasks and brief responses, while others can perform complex reasoning, formulate hypotheses, evaluate alternatives, and construct a genuine response strategy.

Smaller models are also significantly more cost-effective: in contexts involving repetitive, low-variability, or low-criticality tasks (such as message classification, summarizing known content, or generating standard emails), opting for a more economical model may be entirely appropriate. Conversely, when complex reasoning or highly contextualized and personalized responses are required, more advanced models are necessary—along with the computational costs they entail.

1.2. Context: Memory, Documents, and External Sources

The second fundamental element of an agent is the availability of an informational context—that is, the set of data and knowledge the agent can access beyond the initial prompt. This context can take various forms, depending on the environment in which the agent operates and the technologies available. The most common include:

conversation memory, which allows for coherence over an extended exchange;

persistent memory, which retains preferences, historical data, or specific elements related to the user or project;

documents and images provided manually;

access to traditional databases;

semantic knowledge bases, used in RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) systems, enabling the model to search and retrieve relevant information from a document corpus;

ontologies, i.e., structured knowledge models that formally describe concepts and relationships within a specific domain.

The availability of these context sources depends heavily on the operational mode in which the agent is deployed (which we will explore later). If the agent is used in a conversational assistant—such as ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini—the environment natively provides conversation memory, the ability to upload documents, and often, persistent user memory.

If, on the other hand, the agent is embedded within an automated workflow—through tools such as Zapier, Make, or similar platforms—the situation changes significantly. In such cases, one cannot rely on the memory features offered by conversational platforms; context must be managed explicitly. It is up to the automation designer to determine which data to supply to the agent and to construct the appropriate informational environment so the agent can perform the assigned task correctly.

When agents are used in more complex contexts—perhaps across different teams or for diverse functions—it may be advantageous to design shared memories accessible to multiple agents. These structures, however, are complex to develop and maintain: they require advanced competencies, not only technical but also organizational.

In short, the more an agent needs to know, the more critical the context becomes. And the larger the context, the more strategic its design becomes.

1.3. The Use of External Tools

The third fundamental element is the agent’s ability to take action, going beyond mere text generation. Today, agents can be equipped with tools that enable them to interact directly with other software and services.

Platforms such as ChatGPT or Claude have introduced libraries of connectors that provide access to major cloud environments, email systems, and widely used productivity tools—such as Slack, Asana, Notion, and others. This allows an agent to perform concrete operations such as:

sending emails;

generating and storing documents;

updating records in a database;

extracting, transforming, or analyzing data;

managing calendars;

and so forth.

If the goal is to extend the use of agents beyond personal productivity use cases—for instance, to automate business processes or integrate heterogeneous systems—it becomes necessary to leverage workflow management tools such as Zapier, Make, or n8n. These platforms offer thousands of ready-made integrations and enable the orchestration of agents within complex operational flows, combining triggers, transformations, and actions across different systems.

In this context, the agent becomes an active node within a broader system, capable of having a tangible impact on operational activities.

2. The Operational Modes of Agents

Once the fundamental components that define what an agent can do have been clarified, the next step is to understand how these capabilities are actually employed within real-world systems. In other words, it is not enough to know that an agent can interpret instructions, access information, and use tools; one must also determine when and where these capabilities are activated.

Operational modes describe precisely this: the technical and functional context in which the agent is embedded. Three progressive levels can be identified, each with an increasing degree of autonomy and integration.

2.1. The Agent Within a Conversational Assistant

This is the most immediate and accessible mode through which the majority of users first encounter artificial intelligence. The agent is employed within a conversational assistant—such as ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini—and interacts directly with the user through text.

Yet behind this apparent simplicity lies a relatively broad range of operational possibilities worth exploring in detail.

Single, manually initiated conversation. The user opens a new chat, writes a prompt, or pastes a preconfigured setup. They may stop there or choose to add documents, images, or links to provide additional context. Advanced interaction modes—such as deep search—or connectors to external services (cloud storage, email, productivity tools) may also be activated. In this case, the platform automatically manages the conversation memory, user preferences, and any information provided throughout the exchange. The agent responds in real time, dynamically adapting to the flow of the interaction.

Persistent project within the platform. Some environments—such as ChatGPT and Claude, through their Projects feature—allow conversations to be organized into structured projects. Within this context, it becomes possible to define permanent project-level instructions, upload a small, persistent document for all conversations within the project, and maintain a coherent history across multiple sessions. This approach proves helpful when working on recurring topics, with stable requirements and well-defined reference materials.

Customized agents. An additional level of configuration is offered by the ability to create personalized agents within the platforms: Custom GPTs in ChatGPT, Skills in Claude, and Gems in Gemini. In these cases, users can more precisely define the agent’s three core components and create specialized assistants for recurring tasks or more complex business needs.

In all these modes, the agent is essentially employed at an individual level. It remains confined to the conversational assistant environment and is not integrated into a systemic or automated process.

2.2. The Agent Within an Automated Workflow

When an agent is not used directly by a user but is embedded in an automated process triggered by an event, we enter a mode typical of automation tools such as Zapier, Make, n8n, or similar platforms. In this context, the agent becomes a step within a workflow—that is, a chain of actions activated automatically upon the occurrence of a trigger. In this setup, the agent:

does not engage in dialogue with the user;

does not retain conversation memory;

receives structured input (text, data, parameters);

performs a transformation (analysis, extraction, generation);

produces an output used in the next step.

Here is a concrete example:

Trigger: a new customer email is received.

Agent: analyzes the text, determines the intent, and drafts a reply.

Output: the response is sent via Gmail, and the original message is archived in the CRM.

In this case, the agent is not visible to the end user but operates “behind the scenes” as part of an automated operational flow. Its effectiveness largely depends on the clarity of the prompt, the quality of the input data, and the precision with which the agent’s role in the process has been defined.

Unlike the conversational mode, the platform does not manage any memory here. Everything must be configured explicitly. If the agent requires data, it must be provided at the time of activation. Additionally, it is necessary to define a strategy for managing this information and for generating the context correctly. Finally, if the agent needs to interact with tools, it must have the appropriate access via APIs or preconfigured connectors.

This mode represents a significant shift: the agent is no longer an individual assistant, but an intelligent function within a system. In this sense, it can make a decisive contribution to increasing efficiency, reducing operational workload, and improving response quality in repetitive or high-frequency processes.

2.3. Coordinated Agents in Complex Systems

The most advanced and strategically significant level of AI agent use is when multiple agents collaborate within a system—but not according to a rigid, predefined sequence. In this scenario, the agent is no longer a mere step in a static workflow but acts as an orchestrator: it receives an input, assesses the context, defines a strategy, and dynamically activates specialized agents to complete the task.

This is a crucial distinction. In a traditional workflow (as described in the previous section), the process is predefined: an event triggers a predefined sequence of actions. In orchestration, however, the sequence is not fixed; the agent itself determines it based on the nature of the input and the system's rules. The primary agent acts like a project manager: it interprets the problem, evaluates the available options, and selects which resources—i.e., which other agents—to involve.

A concrete example:

Scenario A: A support ticket arrives from a new customer. The orchestrating agent detects that no historical data is available, classifies the request as simple, and initiates an automated resolution process via a specialized response-generation agent.

Scenario B: A ticket is submitted by an existing customer. The primary agent recognizes the need to access historical data, activates an agent to retrieve past interactions, and involves a second agent to assess whether escalation is necessary.

In both cases, the system reacts differently based on the situation, dynamically assembling the most suitable sequence of agents. This is no longer a workflow but an adaptive behavior driven by decision logic.

This architecture—also known as agentic orchestration—is mighty but also poses significant challenges:

It requires advanced skills in prompt design, context management, and agent-to-agent interaction.

It assumes the ability to build robust agents capable of exchanging data in a structured, reliable manner.

It involves accepting the inherent unpredictability of LLMs, which can make guaranteeing system stability harder.

Despite these complexities, the ability to build agents that decide, coordinate, and adapt their behavior based on context opens up new scenarios. It marks a shift from rigid automation to intelligent automation—capable of handling complex, uncertain, or high-variability use cases.

Conclusion

Building effective AI agents does not require deep expertise in artificial intelligence theory or mastery of advanced technologies. What is truly essential is a clear mental architecture: knowing which elements make up an agent and how they can be deployed in real-world contexts.

The model presented in this guide, along with the AI Collaboration Canvas, offers a solid foundation for designing how agents can be integrated into a team. There is no need to start with futuristic solutions: even a well-configured conversational agent can solve recurring problems with excellent efficiency. An agent embedded in an automated workflow can dramatically increase operational efficiency. Complex systems of agents are likely excessive for the vast majority of organizations, which would struggle to manage them.

In conclusion, AI agents are not entities to be idealized or feared, but rather tools that can be designed, configured, and integrated. And they are accessible even to those without a technical background—all it takes is the right mental model to get started.

Curated Curiosity

The Future of Language Tech is Platformized, Not Tool-Based

For anyone working in localization, translation, or multilingual content management, this piece offers a clear and timely perspective. Hilary Atkisson Normanha from Spotify highlights a crucial shift: the future of language technology won’t be defined solely by more powerful models, but by platforms that combine models, context, tools, and workflows in integrated systems.

From the standpoint of localization, this change has several implications:

The focus moves from isolated model quality to the ability to operate within complex, structured environments.

Static translation gives way to dynamic context management—handling memory, tone, terminology, and more.

Linear processes evolve into coordinated interactions between specialized agents (e.g., for segmentation, QA, post-editing, and cultural adaptation).

It’s a helpful reminder that LLMs become genuinely valuable when situated within exemplary architectures, and that much of the innovation in localization will depend on how we design those environments. A thoughtful and relevant read for anyone thinking seriously about the future of content localization.